Lead toxicokinetics following intravenous and oral administration in non–lactating ewe: A preliminary study

Abstract

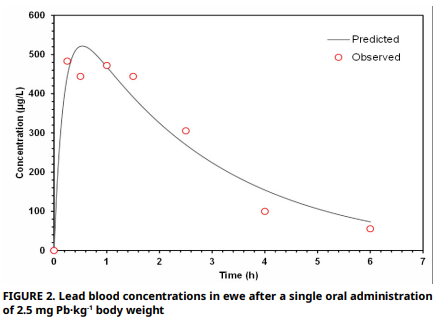

The present study aims to describe the metabolism of the lead in sheep (Ovis aries) by implementing a toxicokinetic approach and to determine the bioavailability. A clinically healthy, one–year–old, non–lactating ewe (40 kg) received a single intravenous dose of lead acetate (0.165 mg Pb·kg-1) followed by oral administration mg Pb·kg-1) after a 40 day w Lead, zinc, copper and calcium levels in the diet were measured before feeding. Serial blood samples were collected over 5 hours (h) (intravenous) and 9 h (oral) and analyzed by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Concentration–time data were fitted to a two compartment model (bicompartmental biexponential for intravenous; biexponential with absorption term for oral) to derive distribution and elimination halflives, clearance, volumes of distribution, mean residence time, area under the curve, and absolute bioavailability. Analysis of ewe feed revealed excessive calcium intake. Following intravenous dosing, lead peaked at 870 µg·L-1, with a rapid distribution (T½α = 0.004 h) and slowelimination (T½β = 6.4 h). Oral administration yielded a lower peak (522 µg·L-1) with absolute bioavailability of only 2% (High dietary calcium likely suppressed gastrointestinal absorption), while steady–state volume of distribution (0.275 L·kg-1) indicated extensive tissue accumulation. The findings highlight compartmental modelling as a critical tool for assessing lead toxicokinetic in ruminants.

Downloads

References

Smith KM, Abrahams PW, Dagleish MP, Steigmajer J. The intake of lead and associated metals by sheep grazing mining– contaminated floodplain pastures in mid–Wales, UK: I. Soil ingestion, soil–metal partitioning and potential availability to pasture herbage and livestock. Sci. Total Environ. [Internet]. 2009; 407(12):3731–3739. doi: https://doi.org/d2dgd3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.02.032

Cowan V Blakley B. Acute lead poisoning in western Canadian cattle — A 16–year retrospective study of diagnostic case records. Can. Vet. J. [Internet]. 2016 [cited Mar 12, 2025]; 57(4):421–426. Available in: https://goo.su/UFCdQO

Darwish WS, Gad TM, Imam TS. Lead, Cadmium and Mercury Residues in the edible offal of sheep and goat with a special reference to their public health implications. Int. J. Adv. Res. [Internet]. 2017; 5(4):189–199. doi: https://doi.org/p89t DOI: https://doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/3795

Bates N, Payne J. Lead poisoning in cattle. Livestock [Internet]. 2017; 22(4):192–197. doi: https://doi.org/p89w DOI: https://doi.org/10.12968/live.2017.22.4.192

Mehennaoui S, Charles E, Joseph–Enriquez B, Clauw M, Milhaud GE. Indicators of lead, zinc and cadmium exposure in cattle: II. Controlled feeding and recovery. Vet. Hum. Toxicol. [Internet]. 1988 [cited Mar 25, 2025]; 30(6):550–555. Available in: https://goo.su/KbqWg

Pareja–Carrera J, Mateo R, Rodrigues–Estival J. Lead (Pb) in sheep exposed to mining pollution: implications for animal and human health. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. [Internet]. 2014; 108:210–216. doi: https://doi.org/f6kk8t DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.07.014

Orisakwe OE, Oladipo OO, Ajaezi GC, Udowelle NA. Horizontal and vertical distribution of heavy metals in farm produce and livestock around lead–contaminated goldmine in Dareta and Abare, Zamfara state, Northern Nigeria. J. Environ. Health. [Internet]. 2017; 2017:3506949. doi: https://doi.org/p89x DOI: https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3506949

Kovacik A, Arvay J, Tusimova E, Harangozo L, Tvrda E, Zbynovska K, Cupka P, Andrascikova S, Tomas J, Massanyi P. Seasonal variations in the blood concentration of selected heavy metals in sheep and their effects on the biochemical and hematological parameters. Chemosphere [Internet]. 2017; 168:365–371. doi: https://doi.org/gwghfx DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.10.090

Johnsen IV, Aaneby J. Soil intake in ruminants grazing on heavy metal contaminated shooting ranges. Sci. Total Environ. [Internet]. 2019; 687:41–49. doi: https://doi.org/gnh4nw DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.086

Payne J. Livesey C. High lead soils: a potential risk to animal and public health. In: Centre for radiation, chemical and environmental hazards. Chemical Hazards Poisons Report. London (UK): Health Protection Agency. [Internet]. 2010 [cited Apr 21, 2025]; 17:42–45. Available in https://goo.su/28MqwD

Pareja–Carrera J, Martinez–Haro M, Mateo R, Rodríguez– Estival J. Effect of mineral supplementation on lead bioavailability and toxicity biomarkers in sheep exposed to mining pollution. Environ. Res. [Internet]. 2021; 196:110364. doi: https://doi.org/gzrq5w DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110364

Sellaoui S, Boufedda N, Boudaoud A, Enriquez B, Mehennaoui S. Effects of repeated oral administration of lead combined with cadmium in non–lactating ewes. Pak. Vet J. [Internet]. 2016 [cited Nov 13, 2024]; 36(4):440–444. Available in: https://goo.su/jOsqs

Milhaud G, Mehennaoui S. Indicators of lead, zinc and cadmium exposure in cattle: 1. Results in a polluted area. Vet. Hum. Toxicol. [Internet]. 1988 [cited 02 Dec, 2023]; 30(6):513–517. Available in: https://goo.su/zTsYz3

Rodrígues–Estival J, Barasona JA, Mateo R. Blood Pb and δ–ALAD inhibition in cattle and sheep from a Pb–polluted mining area. Environ. Pollut. [Internet]. 2012; 160:118–124. doi: https://doi.org/cv6bsw DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2011.09.031

Leggett RW. An Age–specific Kinetic Model of Lead Metabolism in Humans. Environ. Health Perspect. [Internet]. 1993; 101(7) 598–616. doi: https://doi.org/cgsvpb DOI: https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.93101598

National Research Council (NRC). Potential health risks to DOD firing–range personnel from recurrent lead exposure [Internet]. Washington DC (USA): The National Academies Press; 2013 [cited 08 Apr 25]; 198 p. doi: https://doi.org/p9bh

Rădulescu A, Lundgren S. A pharmacokinetic model of lead absorption and calcium competitive dynamics. Sci. Rep. [Internet]. 2019; 9:14225. doi: https://doi.org/p9bm DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50654-7

Mehennaoui S, Houpert P, Federspiel B, Joseph–Enriquez B, Kolf–Clauw M, Milhaud G. Toxicokinetics of lead in the lactating ewe: variations induced by cadmium and zinc. Environ. Sci. [Internet]. 1997 [cited Jun 27, 2023]; 5(2):65–78. Available in: https://goo.su/8UjoBs

Waldner C, Checkley S, Blakley B, Pollock C, Mitchell B. Managing lead exposure and toxicity in cow–calf herds to minimize the potential for food residues. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. [Internet]. 2002; 14(6):481–486. doi: https://doi.org/d73dx5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/104063870201400606

Casteel SW, Weiss C, Henningsen GM, Brattin WJ. Estimation of relative bioavailability of lead in soil and soil–like materials using young swine. Environ. Health Perspect. [Internet]. 2006; 114(8):1162–1171. doi: https://doi.org/b3cffq DOI: https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.8852

Beyer WN, Basta NT, Chaney RL, Henry PFP, Mosby DE, Rattner BA, Scheckel KG, Sprague DT, Weber JS. Bioavailability tests accurately estimate bioavailability of lead to quail. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. [Internet]. 2016; 35(9):2311–2319. doi: https://doi.org/f8zz9t DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3399

Uddin AH, Khalid RS, Alaama M, Abdualkader AM, Kasmuri A, Abbas SA. Comparative study of three digestion methods for elemental analysis in traditional medicine products using atomic absorption spectrometry. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. [Internet]. 2016; 7:6. doi: https://doi.org/gf3tj3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40543-016-0085-6

Zhang Y, Huo M, Zhou J, Xie S. PK Solver: an add program for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics data analysis in Microsoft Excel. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. [Internet]. 2010; 99(3):306–314. doi: https://doi.org/cpg7rf DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.01.007

Fan J, de Lannoy IAM. Pharmacokinetics. Biochem. Pharmacol. [Internet]. 2014; 87(1):93–120. doi: https://doi.org/ggjs9w DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2013.09.007

Aungst BJ, Dolce JA, Fung HL. The effect of dose on the disposition of lead in rats after intravenous and oral administration. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. [Internet]. 1981; 61:48–57. doi: https://doi.org/c69j8w DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0041-008X(81)90006-5

Palminger–Hallén I, Jönsson S, Karlsson MO, Oskarsso A. Toxicokinetics of lead in lactating and nonlactating mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. [Internet]. 1996; 136(2):342–347. doi: https://doi.org/bk7pt2 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1006/taap.1996.0041

Kumar A, Kumar A, Cabral–Pinto MMS, Chaturvedi AK, Shabnam AA, Subrahmanyam G, Mondal R, Kumar–Gupta D, Malyan SK, Kumar SS, A Khan S, Yadav KK. Lead toxicity: Health hazards, influence on food chain, and sustainable remediation approaches. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. [Internet]. 2020; 17(7): 2179. doi: https://doi.org/gjqqg3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072179

Maldonado–Vega M, Cerbón–Solorzano J, Albores–Medina A, Hernández–Luna C, Calderón–Salinas JV. Lead: intestinal absorption and bone mobilization during lactation. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. [Internet]. 1996; 15(11):872–877. doi: https://doi.org/cspkbn DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/096032719601501102

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Toxicological profile for lead. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. [Internet]. 2020; 583 doi: https://doi.org/gnt95d

Mitra P, Sharma S, Purohit P, Sharma P. Clinical and molecular aspects of lead toxicity: An update. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. [Internet]. 2017; 54(7–8):506–528. doi: https://doi.org/gjsdk9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2017.1408562

Oomen AG, Tolls J, Sips A, Van den Hoop MA. Lead speciation in artificial human digestive fluid. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. [Internet]. 2003; 44:107–115. doi: https://doi.org/bqw334 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-002-1225-0

Oehme FW. Toxicity of heavy metals in the environment: Part New York, USA: Marcel Dekker Inc; 1978.

Wu H, Meng Q, Zhou Z, Yu Z. Ferric citrate, nitrate, saponin and their combinations affect in vitro ruminal fermentation, production of sulphide and methane and abundance of select microbial populations. J. Appl. Microbiol. [Internet]. 2019; 127(1):150–158.doi: https://doi.org/p9b4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.14286

Blake K, Mann M. Effect of calcium and phosphorus on the gastrointestinal absorption of 203Pb in man. Environ. Res. [Internet]. 1983; 30(1):188–194. doi: https://doi.org/c92n9f DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-9351(83)90179-2

Aungst BJ, Fung HL. The effects of dietary calcium on lead absorption, distribution, and elimination kinetics in rats. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. [Internet]. 1985; 16:147–159. doi: https://doi.org/brhww5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15287398509530726

Phillips CJC., Mohamed MO, Chiy PC. Effects of duration of exposure to dietary lead on rumen metabolism and the accumulation of heavy metals in sheep. Small Rumin. Res. [Internet]. 2011; 100(2–3):113–121. doi: https://doi.org/fjp86f DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2011.06.004

Deshommes E, Tardif R, Edwards M, Sauvé S, Prévost M. Experimental determination of the oral bioavailability and bioaccessibility of lead particles. Chem. Cent. J. [Internet]. 2012; 6:138. doi: https://doi.org/p9b5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-153X-6-138

Pearl DS, Ammerman CB, Henry PR, Littell RC. Influence of dietary and calcium on tissue accumulation and depletion, lead metabolism and tissue mineral composition in sheep. J. Anim. Sci. [Internet]. 1983; 56(6):1416-–1426. doi: https://doi.org/p9b6 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2527/jas1983.5661416x

Moses E, Ehireme IA. Animal exposure to lead, mechanism of toxicity and treatment strategy – A review. Clin. Case Rep. [Internet]. 2025 [cited 22 Apr 25]; 9(1):1–9. Available in: https://goo.su/NuqiW

Bischoff K, Thompson B, Erb NH. Higgins WP, Ebel JG, Hillebrandt JR. Declines in blood lead concentrations in clinically affected and unaffected cattle accidentally exposed to lead. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. [Internet]. 2012; 24(1):182–187. doi: https://doi.org/bhx9sm DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638711425935

Valtorta SE, Litterio JN, Cerutti RD, Beldomenico HR, Coronel JE, Boggio JC. Daily rhythms in blood and milk lead toxicokinetics following intravenous administration of lead acetate to dairy cows in winter. Biol. Rhythm Res. [Internet]. 2003; 34(3):221–231. doi: https://doi.org/bgrhmc DOI: https://doi.org/10.1076/brhm.34.3.221.18810